|

Mind Over Matter For a pair of Kiwis, Alaskan mountaineering pushes them to the edge... February 5, 2004

Pages »1 2

Most parties "claim" an ascent of the North Face of Hunter when reaching the eyebrow that delineates the junction between the vertical final rock barrier and the summit ice-fields above. Only very few teams have eschewed this crag-climbing mindset and battled on up the easier angled ice to the true summit. Richard and John reached a high-point just one pitch below the easing of the difficult climbing. Their light-and-fast tactics had involved taking less than an optimum supply of fuel. This left them without a functioning stove after the second night, and a resulting disinclination to see out the final 60 meters to an arbitrary summit. Kelly and Johnny fired the lower half of Deprivation, but slowed down on the upper slopes. They abseiled off at the third ice-field rather than sit though an unsupported night on the mountain. Both Kelly and Johnny were non-committal when asked about a repeat attempt. The vertical 120 meter couloir that links the lower grade 4 ice gullies with the first ice-field had proven difficult and dangerous, and for them the justification to climb this section a second time was questionable. Pat and I puzzled over the choice of route and logistical style that we should employ on our own attempt on the North Face of Mt Hunter. We felt that as a team we simply were not burly enough to either hump or haul the big loads, but neither did we feel confident about pulling off a super-light no-bivouac approach. We settled on a compromise: attempt the easier-angled Deprivation route rather than Moonflower, and climb with two nights' worth of skimpy bivvi kit. The lead climber would forge the route carrying a relatively small pack while the seconder dealt with a beefier load. On the crux pitches the leader would give the light pack to the seconder and haul the heavier load. The weather forecast was offering 6 inches of snow in the next 24 hours and little improvement after that. This we studiously ignored. We had altered our thinking from a New Zealand reliance on meteorological signs and forecasts to an Alaskan "suck it and see" approach.

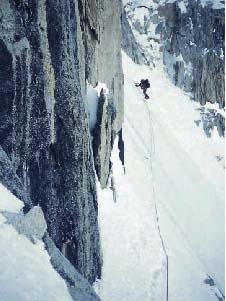

We left our tents at midnight. The pale semi-darkness of an Alaskan night illuminated our hundred-minute uphill ski approach to the base of Mt Hunter. After gearing up, Pat trailed the twin-8 mm ropes through the snow and traversed the three-metre high lower lip of the gaping bergschrund. Marginal tool placements on the uphill side required a controlled lurch in order to surmount the overhanging gap. Seconds after transferring her weight to the upper slope, the entire lower wall collapsed in a huff and rolled downhill to come to halt above my stance. We hooted with laughter at our good fortune. Somehow to me this event seemed to be proof that everything was all right. Our New Zealand mountaineering background was a good foundation for being here, and at last the local scene was becoming familiar. We'd done our Alaskan apprenticeship, brief as it was in my case, and now close-calls like this seemed to be just part and parcel of climbing in this neck of the woods. And as long as Pat and I kept doing what we were doing, then we should continue to dodge the bullets. So it proved. Our ascent of Deprivation was the highpoint of our Alaskan trip. Sure, we suffered, but it was mostly merely physical. While we were fresh we climbed the early WI4 pitches by moving together using running belays, trusting each other's skill through knowledge born of experience during climbs in New Zealand. The crux couloir was an alternating freezing, sweaty, unconsolidated endurance test-piece, but hey, when we broke it down into manageable pieces it was similar to the unprotected short pitches of sastrugi on Ruapehu or the blank leads of snow-ice on Hicks in late June. The ice-fields were a form of climbers' hell: pitch after pitch of calf-wrenching, gut-busting polished steel set at 50 degrees. But stuff like that is just a body work-out, and by setting our minds free and focusing on the future we were able to stick to the plan.

At the top of the vertical final pitch we hung from the first of forty-something V-threads. It was time to stop suffering; to stop swinging blunt ice-tools, stop bashing bruised knuckles, and stop kicking our stubbed toes into iron-hard ice. It was also time to stop wondering if we could do it. We basked in the satisfaction of overcoming much more than the physical hardships of the climb. Even more gratifying was the knowledge that we had overcome the uncertainties inherent in such an undertaking, and had proven to ourselves that mind over matter can win out.

Courtesy of New Zealand Adventure

|

||||||||||||||||